The effects of a less-than-diverse media workforce

By Amanda Ghazale Aziz

When Carleton University asked reporter Judy Trinh to give a talk on diversity in the journalism industry to students in the journalism and communications program, she said yes.

She suspected why the university had asked her: She works full-time for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC), and she’s not white. Even with some reservations, she took the speaking opportunity with a plan in mind.

Up to this point, high schools had been her regular venues to give lectures about journalism. When these schools had asked her to present on diversity, it was always about women in journalism, not race. Carleton’s request was a first.

Carleton’s invitation was an opportunity for Trinh to encourage racialized students to pursue a career in journalism. She truly believed that diverse representation in newsrooms matters, and the first step would be to start an honest discussion on race and the Canadian newsroom. If these students were going to build a meaningful career in media, then they would have to know the full truth.

In a visual slideshow presentation, Trinh presented a comparison of statistics from a study in the Columbia Journalism Review: 49 per cent of minority journalism graduates find a job in journalism, compared to 66 per cent of white journalism graduates. This is the reality for Black, Indigenous and people of colour (lumped into one vague group as “minorities”) who want to break in this industry in the U.S.

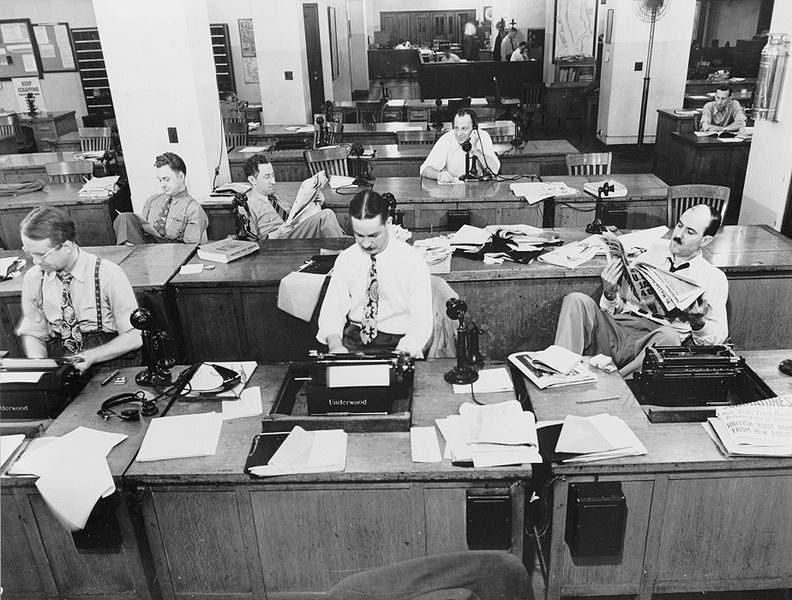

A now infamous Laval University study in 2000 had found that 97 per cent of journalists at that time were white. For Trinh, the lack of in-depth reporting on non-white cultures was the sad consequence of the statistic.

“In terms of access, in terms of building trust,” said Trinh. “If you have visible minorities in your newsroom, those ties are stronger.

“When you don’t have those ties, it’s much more difficult to get into those communities and cover them, because there is always a sense of distrust as an outsider.”

Gaining access to racialized communities and reporting on their cultures in more depth are two of many reasons that Trinh thinks that newsroom should be trying to diversify more. A white journalist could conduct thorough research for a piece on a racialized culture and community but there would still be missed nuances.

Even despite these obvious advantages, the statistics suggest that employers still don’t get it. Recently, the CBC came under fire from CANADALAND for not abiding by the Multiculturalism Act’s guidelines on equal opportunity employment for racialized folks. According to the report, a staggering 90–93 per cent of CBC staff were white whereas according to Statistics Canada only around 75 percent of Canadians are white. What’s unsettling in this report is the possibility that employers aren’t compelled to address their discriminatory hiring practices.

Currently, the Multiculturalism Act, along with the Employment Equity Act, is the driving government legislation when it comes to ensuring diverse representation in the newsroom — and the act only applies to newsrooms that are publicly funded. Even then, the act isn’t so heavily implemented as it should be, nor is it fit to match our racial climate today.

The act was written in an era that believed it had achieved a post-racial society. Pierre Trudeau introduced the idea of a Multiculturalism Act in 1971, and Brian Mulroney ratified it a decade later.

Today, however, one in five Canadians identify as a visible minority and we aren’t embracing multiculturalism as much as we think we are. A recent poll by the CBC and Angus Reid shows that 68 per cent of Canadians believe “minorities should do more to fit in with mainstream American/Canadian society,” indicating access to diverse media representation is lacking.

And the Multiculturalism Act itself hasn’t been as accessible as it should be. The language of the act itself is dependent on a dated sense of what equality is, which gives the idea that the act is one size fits all for everyone:

“3 (1) It is hereby declared to be the policy of the Government of Canada to (e) ensure that all individuals receive equal treatment and equal protection under the law, while respecting and valuing their diversity;”

Yasmin Jiwani, a communications studies professor at Concordia University, has been researching the relationship between policy and media over the last few years. In a project with other researchers, Jiwani carefully looked at how Indigenous youth and Muslim youth were portrayed in a three-year time frame at The Globe and Mail. They saw that stories on these groups typically fit narratives such as either “Youth in Trouble” or “Youth as Trouble”, while non-Indigenous and non-Muslim youth were often portrayed as overachievers and young entrepreneurs.

“What my research has shown,” said Jiwani, “is that when we do see people of colour in the media we only see them as ‘problem people’—people who are criminals, people who are taking advantage of Canadian benevolence, or people who are out in war zones.”

“If you are a policy-maker, who most likely doesn’t always encounter folks who are marginalized, what does the press tell you? It tells you that these are ‘problem people’ and they don’t belong in our nation.”

Canada likes to hail itself as a multicultural mosaic. And with Donald Trump’s win in the U.S. election early this November, many citizens have been taking the opportunity celebrate Canada’s apparent superiority—forgetting that the country is rampant with its own problems.

After Trump’s victory, Kellie Leitch—who is currently running to be the leader of Canada’s Conservative Party—sent out a mass email calling Trump’s victory an “exciting message that needs to be delivered in Canada as well.”

Before the 2016 U.S. election, she’d already announced plans for tougher screening processes for immigrants and refugees and was promoting the Conservative Party’s idea of creating a “barbaric cultural practices” tipline for the RCMP, which she later said she regretted.

You don’t have to look far online or in print to notice that we’ve fallen short of our nation’s ideal of equality and multiculturalism. Is Canadian journalism today operating under an act that depicts not only an aged view, but one that is unrealistic in its depiction of what multiculturalism is? It’s unclear how employers are required to fulfill their obligations under the Multiculturalism Act and the Employment Equity Act in their workplaces.

Shree Paradkar said it best in her Toronto Star column: “Non-representation in journalism is a form of oppression. It happens when we—Canadians—invite or accept newcomers to our mutual benefit, but then allow only one dominant group—whites—to play gatekeeper to all the stories, generation after generation. Indigenous people, too, are not exempt from exclusion.”

Equally, there is anxiety about newsrooms using racialized writers as tokens instead of addressing changing their overall hiring practices. Jiwani said she is concerned about the trend of news organizations hiring racialized writers to report exclusively on diversity. She calls these token writers “race ambassadors.”

Denise Balkissoon, currently the editor of the life section at The Globe and Mail, recalls that early in her career pitches concerning race and diversity were often shut down. Now she sees the opposite happening. Emerging journalists are being offered the chance to write on these topics. The dilemma, though, is that the opportunity doesn’t extend beyond that assignment.

“Usually a young journalist of colour will get tapped to write a sensationalist story and that story will turn out great,” Balkissoon said. “But then that journalist doesn’t get hired as a staff writer or nurtured to be a well-rounded writer.”

“People have figured out,” added Balkissoon, “that diversity is relevant at a time when there’s no money dedicated to hiring anyone.”

Along with being an editor, and writing a column, Balkissoon is the co-host (with Hannah Sung) of the Colour Code podcast. Colour Code was first conceived after The Globe and Mailgave workers the opportunity to apply for a special projects fund.

The idea for the podcast was originally about Canadian identity but shifted to focusing on race and Canada. “Our goal was not to prove that racism exists,” said Balkissoon, “but that it was already assumed.”

There were already plenty of American podcasts out there on race, and Balkissoon and Sung wanted to do something just as “meaningful and hard-hitting.”

While some white listeners reached out to Balkissoon and Sung to thank them for helping them learn and to re-examine their privilege, others sent hate mail—especially when the show tackled difficult topics. A particularly large amount of hate mail followed the episode “Eggshells,” in which Balkissoon revisits a heated discussion she had on assimilation at CKNW, a radio show in Vancouver. That backlash inspired her column piece, “We all profit from soldiers on the front lines of hate.”

Readers also have responsibility over what they want to get out of a newspaper since they choose what content and publications they read. Balkissoon insists that people who are interested in good journalism should also not hesitate to “tell the people who run it that diversity is important to them.”

She also sees that importance being reflected on their financial contribution, and how it’s contingent on progressing journalism. After starting the crowdfunded digital magazine The Ethnic Aisle with a group of friends, she was surprised over how many people responded with interest to an online publication solely focused on race and ethnicity.

“[The Ethnic Aisle] was envisioned as a side-conversation,” said Balkissoon, “because when I had first joined Twitter I found myself getting into conversations about race in a way I had never before. And then it also became a way for younger journalists to get practice in pitching and to get practice in editing.”

Beyond small publications, spaces for young and racialized journalists to flourish can be hard to find.

Second-year journalism student Andrew (whose name has been changed to protect his identity) finds himself completely alone in the concentration of his program as the only person who identifies as Black.

When he considered going into radio, he was cautioned by the program staff about how the medium was “unbearably white.” His instructors had another recommendation. “They asked me, why would you want to stay here? Toronto has a bigger market—which I kind of get,” he said.

“But it was as if they had wanted me to be the lone Black reporter for a while and then leave for a larger city. The question is, are they really making an effort to attract people to the East coast to work here? Or are they looking for what’s good ‘locally?’ As in hiring what locals want, as they aren’t interested in seeing people of colour in the media.”

As he carries on with his studies, Andrew still plans to continue airing out concerns to his school’s faculty. These are discussions that are frank, he adds, but necessary.

It’s becoming more and more obvious to the public that, in attempts to address this issue, racialized folks are finding a way to speak out. For the last issue of The Ryerson Review of Journalism, the masthead chose diversity as its main focus. Every single article inside the print issue was dedicated to that theme. “Because it’s 2016” was plastered in bold text on the front cover.

And while the year is nearing its end, the discussion is far from over.

This story was originally published on belaboured, and is publised under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Amanda Ghazale Aziz is a student at the University ofToronto, and is a senior editor at the Intersections: The Clapback Journal and associate editor at Acta Victoriana. In 2014-2015, she was one of the Editors-in-Chiefs atThe Strand, and has also contributed to The Varsity, CWA’s Media Works Guide as well as with other publications. Sometimes, she writes on napkins before using them. You can find her as a part of Badass Muslimah's upcoming podcast and as a member of Femifesto.ca.