Why do people go to journalism school? The obvious answer is that they want to be journalists.

Of course, journalism educators know this isn’t universally true. Students go into journalism programs with a fairly wide variety of career aspirations. A survey I conducted with Ryerson professor Anne McNeilly of journalism students at Carleton University and Ryerson University in 2015 found that just over 82 per cent of undergraduate students in the first year of their programs said they wanted to work in journalism.

By some international measures, this is a high percentage. But a close look at this data suggests the picture is very different by the time students get to the fourth year, at which point journalism educators are teaching two (or more) different groups of students.

Researchers in other countries have found that students in journalism programs have many different career aspirations. Researchers in Britain, for example, found that only about three-quarters of beginning journalism students wanted to pursue a career in journalism. Researchers in Brazil found that nearly 40 per cent of journalism students wanted to work in public relations at the end of their programs. Many studies, including the British one, have also found that journalism students become somewhat less likely to want to work in the field at the end of their programs than at the beginning.

We have found a fairly similar pattern in Canada. In our 2015 survey, we found that while 83 per cent of first-year journalism students either “absolutely” or “likely” wanted to pursue a career in journalism, just under 55 per cent of fourth-year students said the same thing.

According to our survey data, students with a desire to work in different fields appear to have very different attitudes towards journalism job characteristics than those who want to work in the field. The data, first analyzed in 2019, is based upon two surveys of Ryerson and Carleton journalism students, one conducted in 2015 (with 638 respondents) and a very similar one in 2017 (with 316 respondents).

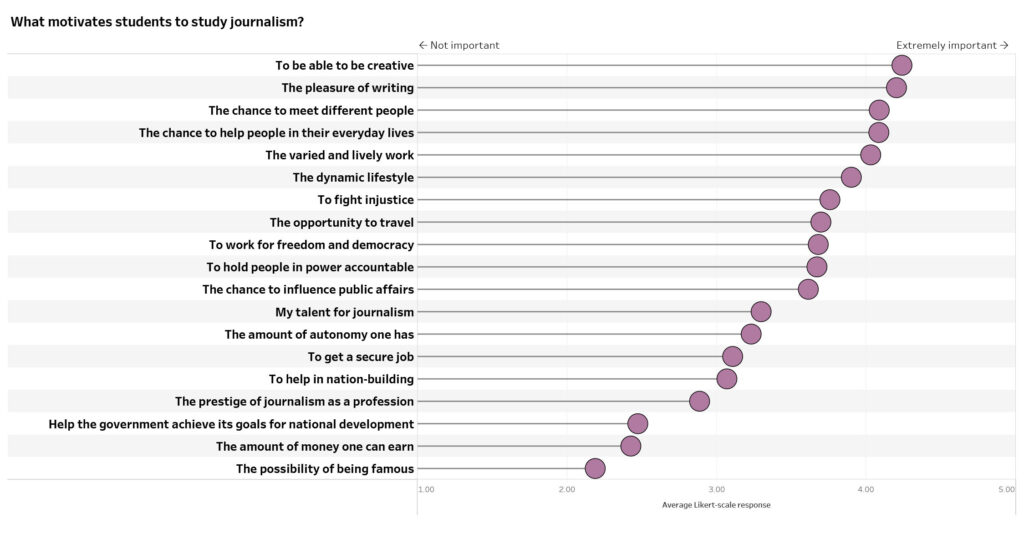

One question in both surveys asked students to rate the importance of different factors that may have motivated them to study journalism, which was done on a five-point scale from 1 (not at all important) to 5 (extremely important).

Results illustrate what has also been found in different international studies, namely that students who study journalism report being motivated more by a desire to write and be creative, as well as perceived job characteristics (varied and lively work, the chance to meet different people, dynamic lifestyle) than by characteristics associated with the role journalists are often thought to play in society (fight injustice, hold people in power accountable, etc.).

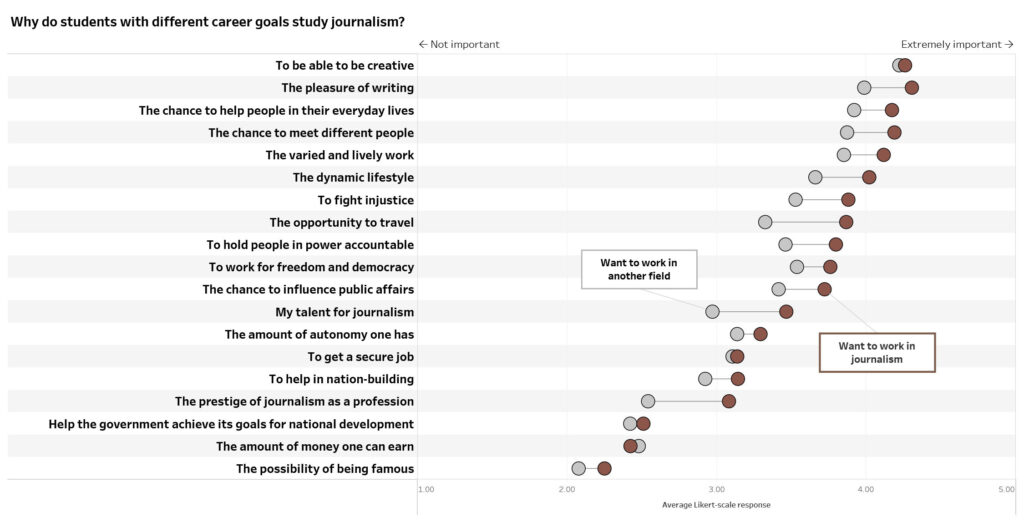

However, there are differences between the students who say they want to work in journalism and those who say they want to work in other fields.

While both groups gave nearly identical responses on the “creative,”’ “secure job” and “money” factors, overall the journalism group rated most factors more highly than the non-journalism group – a result that isn’t hugely surprising since the questions are geared around journalism characteristics. However, this picture still doesn’t tell the whole story.

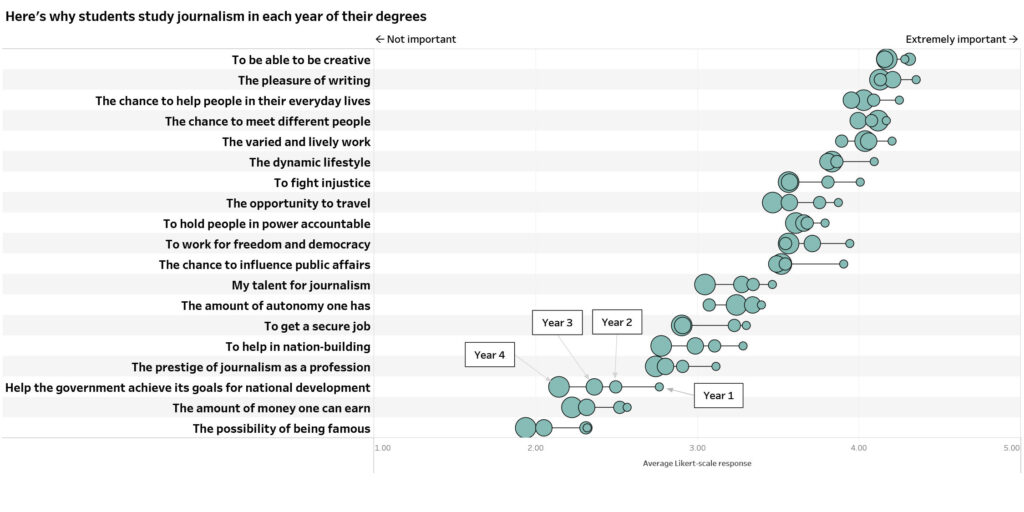

Responses to the motivation factors change (sometimes considerably) depending on which year of the programs the respondents are in. In general, average responses tend to drop between first-year and fourth-year students, as was found in some other jurisdictions.

In this graphic, the smallest sphere indicates average responses for students in the first year of the program. The spheres get progressively larger through the subsequent years, with the largest spheres indicating responses from fourth-year students.

As illustrated, all motivation factors tend to drop over the course of the four years of an undergraduate degree, though the drop is not necessarily linear. For example, the “pleasure of writing” factor drops between the first and second years, rises slightly in the third year then drops slightly in the fourth.

Factors such as fighting injustice and working for freedom and democracy drop after the first year. Some researchers hypothesize that first-year students have more idealistic perceptions journalism.

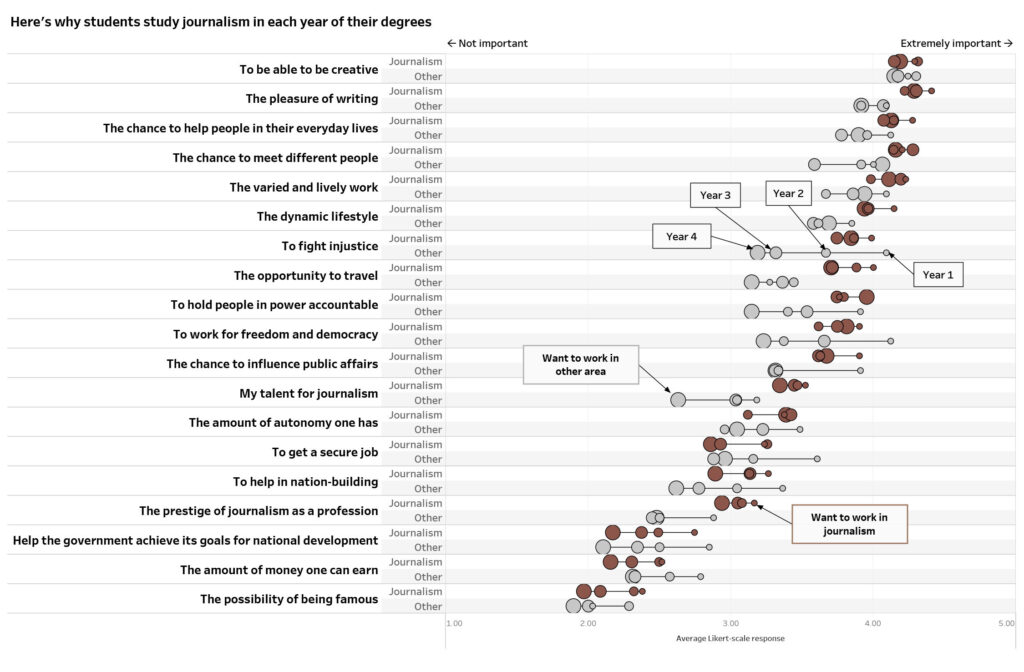

But again, there are differences in the responses depending upon whether the students indicate a desire to pursue a career in journalism.

The motivation factor related to creativity is very similar for both groups, with only slight differences across the different years. This suggests that both groups view journalism programs as a path to a creative occupation, which may help explain why journalism programs are attractive to students even though they want to pursue careers in other fields.

The differences become much more pronounced when it comes to fighting injustice, working for freedom and democracy and holding people in power accountable. In all three cases, those who want to pursue careers in journalism are fairly consistent over the four years with average response values clustered just under 4 (very important), while those who report wanting to work in different areas saw a steady decline in importance from just above or below 4 in their first year to just above 3 in their fourth year.

For the non-journalism group, the drop in average responses to the “holding people in power accountable” factor is large enough that it makes it appear that this factor drops for all students in the survey, as illustrated in the previous graphic. In fact, the average response actually rises for those who say they want to pursue a career in journalism.

This phenomenon has some potentially significant implications for journalism programs and educators. It’s no secret that the news business has been in rough shape for many years; stories about layoffs and down-sizing are all too common.

April Lingren, Ryerson journalism professor and Local News Research Project principal investigator, and her team have tracked an alarming decline in local news outlets in Canada. You can’t blame students for making a strategic decision to enrol in a journalism program with the intention of working in a different field or making that decision part-way through their programs.

According to my earlier analysis, having work experience appears to be correlated with a higher interest in pursuing a career in journalism. But it’s possible that the non-journalism group could eventually outnumber the journalism group, whether because paid work experience in journalism is harder to come by or for other reasons.

Journalism programs where a majority of students are strongly motivated by a desire to write and do something creative but decreasingly motivated by more fundamental journalism values could be a challenging environment.

Upper-year workshops oriented around producing local news, for example, may not be as appealing to the non-journalism as the journalism group. We may need to be more aware of what students want to get out of their journalism programs, especially as the news media landscape continues adapt to digital realities.