This story was funded by the J-Source Patreon campaign

By Tamsyn Burgmann

Bhumika Shrestha gazes ahead with attentive eyes, shifts in her seat and awaits the first question: “Did you always know you are transgender?”

She takes in the question for a moment, and then replies, that she was born a boy but has behaved “girly” since she was five or six. She describes a childhood of dressing up and helping her mom and then, after a split-second pause, says sometimes her family gets threatened. She pauses almost imperceptibly again, then says she’s luckier than most transgender people in Nepal. Her family accepts her female gender identity, she says, “but most of the transgender families, they always have problems.”

It’s a rare conversation with the 29-year-old Nepalese activist, yet one that could continue for hours or resume any time from anywhere. There’s only one caveat: you must be connected to the Internet. That’s because the person on the screen isn’t live. What you see is a recording of Shrestha, her answers stitched together by Artificial Intelligence, high-end video production, voice recognition and natural-language processing.

The bot’s creator is Marc Lajoie, a journalist from Montreal, now based in Hong Kong, who specializes in innovative media projects. And Lajoie works for an unlikely ally — China Daily, the Communist country’s government-owned newspaper, which published the project online last fall.

Why would a traditionally conservative mainland China media giant publish an AI project about a transgender woman in Nepal? Lajoie believes “the cool factor” may have melted any resistance.

“People are a little more willing to open their minds to something that is ground-breaking,” he said. “And if you can break ground on the technological side, maybe you should be able to break ground on the editorial side as well.”

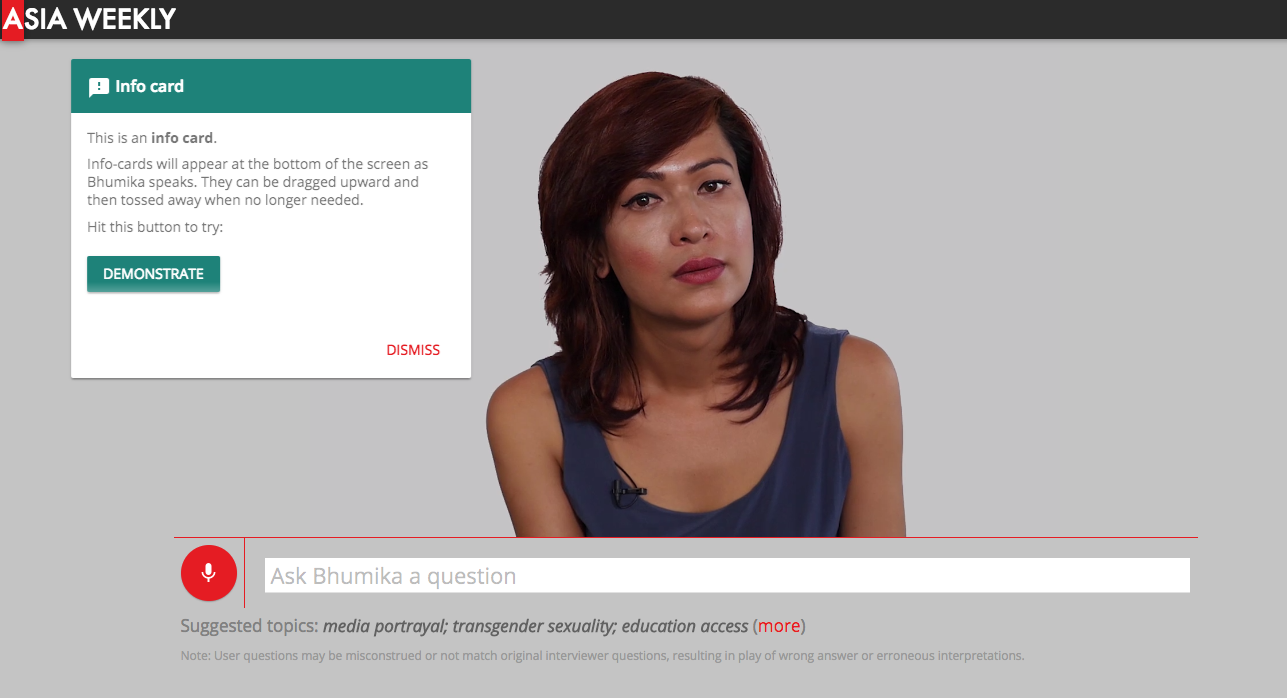

Users can access “Bhumika Can Speak For Herself” with a smartphone or computer and ‘converse’ with her by way of voice-recognition software or typing. The bot analyzes your question and then pulls together an answer by instantly clipping together portions of a series of in depth pre-recorded interviews.

It has also given the real Shrestha, an elected member of the democratic Nepali Congress party, a virtual stage to tell her personal story in perpetuity. In October 2015, she became the first Nepalese person to travel using a passport with the gender category marked “other.” Nepal amended its constitution in 2011 to recognize a third gender.

Shrestha believes Lajoie’s use of advanced technology could help propel LGBTQ rights in China, too. In a Skype interview she said “hidden” transgender people in China might be emboldened upon learning about progress in Nepal, which shares the mainland’s southwest border.

“If they see the video, they have empowerment and they can come out themselves,” she said.

Lajoie similarly hopes the technology will attract audiences who might have shied from the subject. As stories about transgender people have gained traction in Western media, he noticed a dearth of Southeast and South Asia voices, despite the region’s history of accommodating diverse gender identities.

“I could kind of trick (people) into viewing it. Because they would want to play with a cool toy,” he said.

But he had to leave himself out.

“I am the exact opposite of Bhumika. I’m a straight, white, male, cis-gendered person from a rich country,” said the 37-year-old. “So that’s exactly why I didn’t want to frame what she was saying.”

To ensure the project remained journalistic, he produced screen pop-ups, called “info-cards,” to provide context or challenge any of the bot’s more political replies.

Digital expert Darcy Christ, originally from Toronto, said he’s never seen AI used this way before, but even more innovative is how the technology makes the journalist invisible.

“The more traditional narrative is changing,” said Christ, a lecturer at the Journalism and Media Studies Centre at the University of Hong Kong.

The technique came first. Lajoie only set off for Kathmandu after developing and test-driving enough of the software needed to bring the bot to life. His vision was akin to giving Apple’s iPhone-assistant Siri a face. He wanted a source who would candidly share a unique life experience that embodied a bigger issue.

His search for a high-profile transgender person in Asia led him to Shrestha.

“I kind of gambled. I went to Nepal and really hoped. She had said that she was willing,” said Lajoie, who travelled from Hong Kong in July.

He stayed two-and-a-half weeks, spending two full days interviewing Shrestha with a translator and high-end video equipment. When he couldn’t find a production studio, he rented space in a nature-themed guesthouse run by a Sherpa once named the youngest person to climb Mount Everest. Shrestha sat on a tree stump.

Back in Hong Kong, Lajoie trimmed the footage to just under four hours and sliced it into 381 segments. He then applied IBM’s Watson Services, an AI technology platform. When a user asks the bot a question, the Watson platform selects which segments to glue together for on-the-fly answers.

“It doesn’t always get it right, but it does pretty well,” Lajoie said.

Lajoie said he was proud to see online banners prominently advertising it on China Daily’s mainland website. His editors gave him a “long leash” and there was “zero” political interference, he said.

“I expected to have a bigger fight on my hands, not to receive as much support,” he said, noting he was given three months to do the work.

Darcy Christ, however, believes the project was given more leeway because its subject isn’t actually Chinese. Unusual technology will flummox censors for only so long, he said.

“Even if your technology is helping something get under the radar … I think it only gives it a short run, a little bit of room to move than a traditional piece.”

It’s when something gets too popular that authorities have moved to shut things down, he added.

Lajoie said the progressive project has received plenty of positive attention so far, including a push on Weibo, a Chinese-language microblogging site with hundreds of millions of users. He’s convinced the high-tech element lowered barriers.

“If you’ve got something cool enough, you can tell stories that people would never accept otherwise.”