Ryerson professor Joyce Smith writes about her innovation workshop at the university's journalism school, and how even if the project fails, a student who experiments can succeed.

By Joyce Smith

It’s no surprise that I agree with Maija Saari’s recent piece on innovation on J-Source.

Full disclosure: we graduated from the same UWO journalism class and both took Peter Desbarats’ creative writing course. Apart from allowing us to exercise our imaginations and publish our own short story collection, I will always thank him for introducing us to creative people, notably novelist/journalist Joan Barfoot, and the incomparable Greg Curnoe. A few hours spent in Curnoe’s studio surrounded by jazz, bikes and self-portraits deeply influenced my thinking about creators who are curious, engaged and wide-ranging in their interests. He clearly loved trying things, some of which produced art gallery worthy results, and others intangible hours of pedalling in the southwestern Ontario air. Each activity fed the other.

Working on curriculum for online journalism taught me another important lesson: take time to decide what will survive change. When I started teaching at Ryerson in 2001, Twitter was unknown. Now it’s an important part of any course. It’s not the hashtag that counts, but the need for verification, concise writing and engagement. When archaeologists find stone tools, the objects are interesting. But more compelling is what they suggest about the tool-maker’s ability to identify a task, conceive of ideas and create solutions.

This should be our approach. Rather than begin with the premise that designing a new smartphone app or a Big Data graphing program will teach innovation, why not learn to tackle any kind of future challenge, be it technological, economic, or philosophical?

Related content on J-Source:

- Opinion: J-schools should innovate by prioritizing research and discovery instead of waiting for industry to dictate its needs

- Opinion: We Need a Digital-First Curriculum to Teach Modern Journalism

- Applying innovation to journalism curricula

Caption: The Red Canoe group (online literacy for young people project) describing their project. From left: Dean Gerd Hauck, Zoe McKnight, Angela Hickman, John Honderich, Wendy Gillis, Ashley Csanady.

When planning our MJ program, many of us were taken with Mitchell Stephens’ remarks that j-schools do a good job preparing students for the status quo, but aren’t so good at experimentation. Higher education should provide a safe environment to try – and sometimes fail at – new ideas and methods. And so Ryerson’s curriculum includes Journalism Workshop, a required course for all second-year MJ students.

After reading a lot about pedagogy (especially as employed in design fields), I decided on a process common to problem-solving competitions. (Yes, I admit. I did this in high school. But it’s also the model for things like the Knight News Challenge.) I like “creative problem-solving;” the marriage of something artistic with something practical suits journalism. To be honest, “innovation” for me is a term so stretched in its usage as to become almost meaningless.

Here’s how I teach my Journalism Workshop: Groups of four students identify a challenge facing journalism, prototype a solution, and then (with the support from the Ryerson Journalism Research Centre) present the idea to news leaders. Apart from producing a prototype, the course introduces and reinforces lateral thinking and team-work, research skills, creative brainstorming exercises, budgeting and marketing. Students are evaluated not only on the final product, but on their willingness to engage in the underlying process. Even if their prototype fails they can succeed, so long as they experimented. This in itself is a shift in thinking. Rewarding students for playfulness, for trying things outside their comfort zone, is counter to most evaluation.

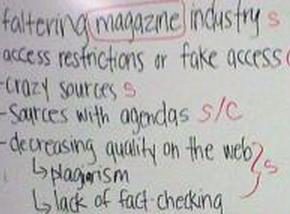

Caption: Workshop students begin by identifying problems worth solving.

Briefly, here are the steps:

- Identify challenges. Are these core challenges, or symptoms of something else? Think of the television show House and differential diagnosis: is the nosebleed the problem to be solved, or is it indicative of hypertension? Is declining readership for print newspapers the problem, or is it indicative of apathy? Low literacy levels? Allergies to newsprint? We may think we know the answer, but in jumping to it prematurely, other possibilities get closed off. It’s one of the reasons I don’t ascribe to courses which begin with the solution (let’s make this app). It’s also a process which parallels news judgment. Is the story really about the dangers of fairground food, or is it about public health inspections? Or a willingness to eat just about anything?

- Research the hell out of the issue. This includes investigating how other sectors have approached similar problems. Cross-pollination is often at the root of successful innovation.

- Decide on and prototype a solution. Any problem worth solving should generate numerous responses, some better at addressing the particular context. Students don’t need to cure all that ails journalism. They need just one, dynamite idea that delivers on what it promises.

- Sell it. How many good story ideas get short shrift because the person pitching them does a crappy job convincing their editor/producer? Same with innovative ideas. Our grads need to know how to sell their ideas, and in so doing, their own competency and creativity. We’ve been lucky to have great industry partners who give up a few hours to provide the students with constructive feedback.

[node:ad]

What delights and encourages me is that while over the past four years many of the same challenges have been identified (shrinking newsroom resources, lack of public trust), students come up with new solutions. These have included everything from newsroom reality shows to bundling programs for paywalls to clever coffee-cup sleeves. A creative problem-solving process produces not just innovative things, but also methods and organizations.

What of instructor innovation? Creativity thrives in safe surroundings, where trying seemingly crazy approaches won’t result in humiliation. By the end of two years together, the 28 students are supportive of each other, making life easier for me. But I’m more than willing to be creatively silly. I’ve tried knitting, theatre-sports, and working with pipe-cleaners. Some things haven’t worked, but music always does: Every year students amaze me with songs about their projects, lyrics written and performed in under two hours. Rap, spoken-word haiku, accompanying interpretive highland dance… it’s surprising and impressive, even to them.

Caption: Prototype for the POV Cafe, mock-up created by Ryerson Interior Design student, Anna Wong.

One of the toughest things is the not-always-unspoken “How will doing this silly stuff get me a job?” which is the j-school equivalent of “Will this be on the exam?” I think it’s sad that students feel so pressured by debt and the job market and even our own curricular demands that they find it hard to relax and experiment. I’ve tried responses to this: appealing to the latest in neuroscience and creativity, citing examples from Google’s 20 percent time and creative courses taught at business schools. Being innovative takes time, and that time has to be somewhat flexible and open-ended.

This course has made me incredibly proud and reduced me to tears. I’ve had feedback saying it was the best MJ class, and received student course evaluations which left me feeling punched in the gut for days and happy to have tenure. Some students will never see the benefit in spending time thinking about thinking when they could be practising their reporting skills. But I’ll keep trying to find better ways of teaching this course about which I feel so strongly. It’s a bit of a meta-exercise, trying to creatively problem-solve how to teach a course on creative problem-solving. And a bit ironic when many innovators encourage failing early and often. Which teacher among us wants to admit from the start that by trying a slew of new things, we’re going to fail at some? It’s tempting to stick to polishing-up lectures that work.

But one of the things we discuss in class is how to define and measure success. I try to concentrate on the students’ glowing final presentations of their ideas. This is at least as worthy a marker as my course evaluations.

Of course, the most important mark of success should be in the future. If our grads draw on creative problem-solving methods as they tackle both the daily and long-term practice of journalism, it’s been worthwhile.

This kind of course may not get a student a job, but it should help them keep a job, and keep our collective profession evolving in healthy and creative ways. While journalism educators should respond quickly to the latest disruptions and innovations, I’d like to think that we’re in this for the long haul.

Joyce Smith is an associate professor at Ryerson University.