Journalism students are in a precarious position when it comes to social media. On the one hand, some recent research suggests that social media skills are in very high demand in Canadian newsrooms. On the other, certain uses of social media could make it even more difficult for these students to land journalism jobs in the first place.

One of the most contentious areas revolves around what most people on social media appear to take for granted: freely expressing opinions about people and events in the news.

Most large newsrooms have policies relating to journalists’ use of social media in this regard. The CBC’s Journalistic Standards and Practices, for example, states that “the expression of personal opinions on controversial subjects, including politics, can undermine the credibility of CBC journalism and erode the trust of our audience. Therefore, we refrain from expressing such opinions in profiles or posts for any account which identifies or associates us with CBC/Radio-Canada.”

Similarly, the Toronto Star’s Newsroom Policy and Journalistic Standards Guide states that “journalists who report for the Star should not editorialize on the topics they cover through social media or online comments as readers could construe this as evidence that their news reporting is biased.”

So it should come as no surprise that newsroom leaders in Canada would take a dim view of prospective job candidates who do stray from that prescription.

In one of my recent studies, I asked newsroom leaders in Canada about the kind of technology-oriented skills and capabilities they expect of recent journalism graduates. (The survey was conducted in early 2018. In all, 119 newsroom leaders were contacted by email and invited to participate in the survey. A total of 67 took the survey, a response rate of just over 56 per cent.)

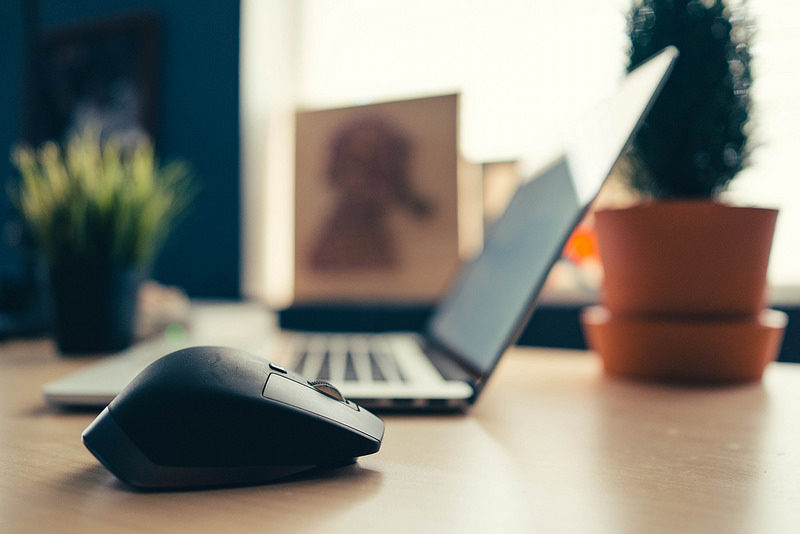

Among other things, newsroom leaders were asked whether a social-media profile where a job candidate freely expresses opinions on news events of the day would be considered an asset, a liability or neither.

Nearly 54 per cent of respondents said they would consider such a profile a liability, compared with 11 per cent who said it would be an asset and nearly 35 per cent who said it would be neither.

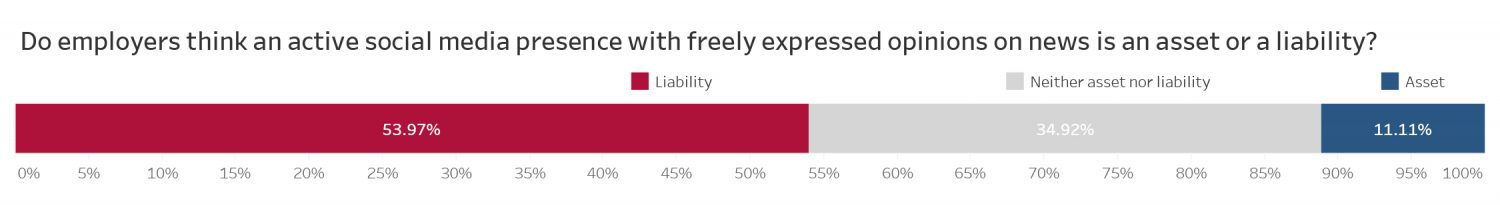

At the same time, it appears that having an active social media feed is a relatively important consideration for job seekers. Just over 45 per cent of respondents said it is either extremely important or very important. Less than seven per cent indicated that it was of little importance (4.7 per cent) or unimportant (1.6 per cent).

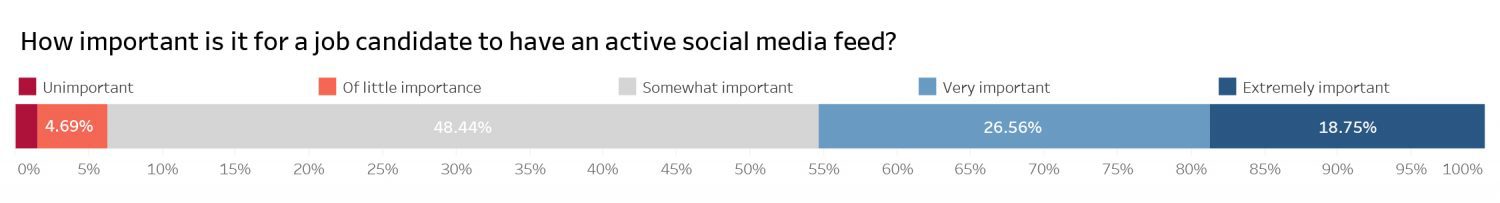

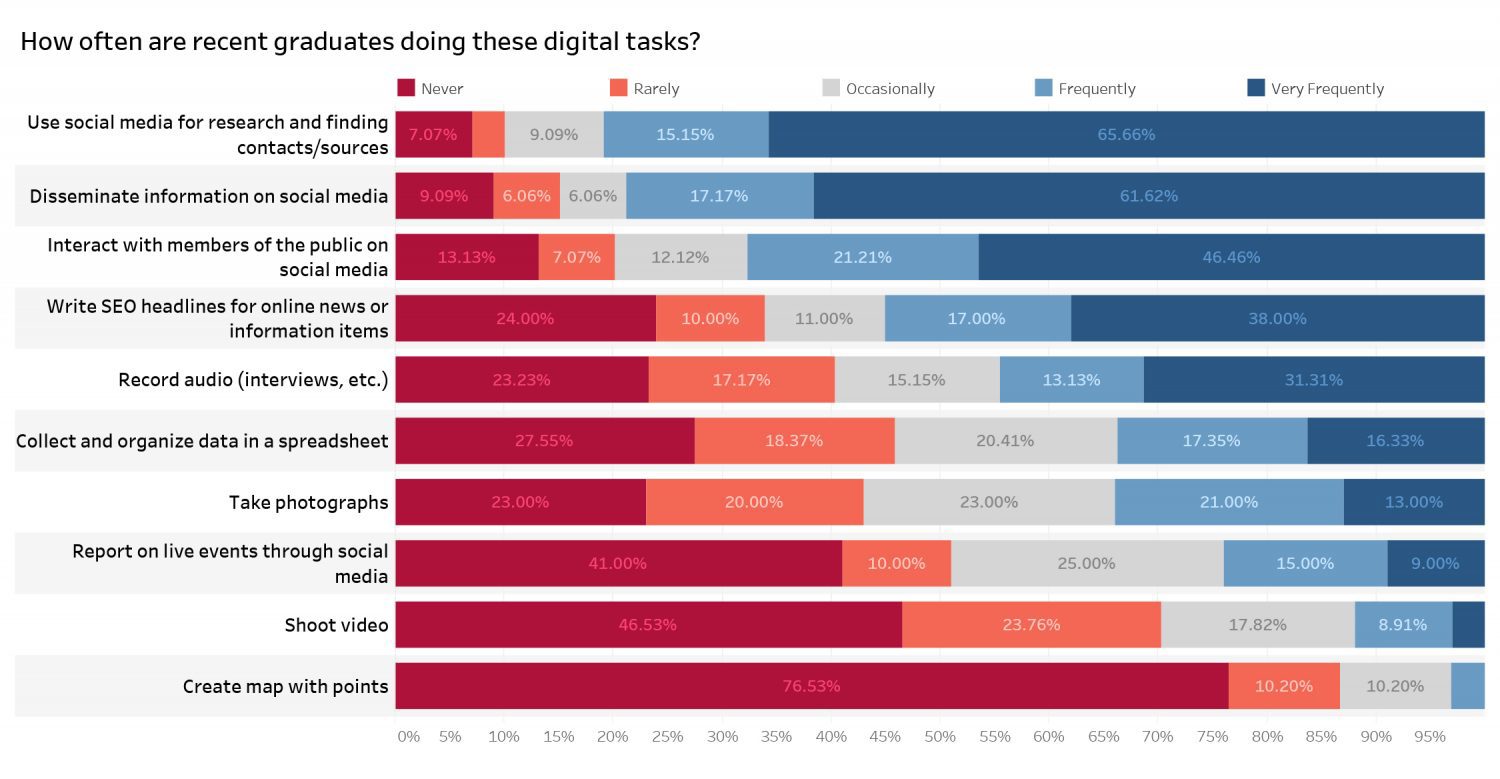

Once young journalists find positions in Canadian newsrooms, they can expect that social media will be a regular and important part of their jobs. The same newsroom leaders were asked about what kind of technology-oriented tasks they expect young journalists to perform as part of their jobs. Tasks related to social media were expected to be performed the most frequently.

In a twin survey of recent graduates from a large university journalism program (the survey was also conducted in the spring, 2018, and had 114 responses with a 32 per cent response rate), respondents painted a similar picture.

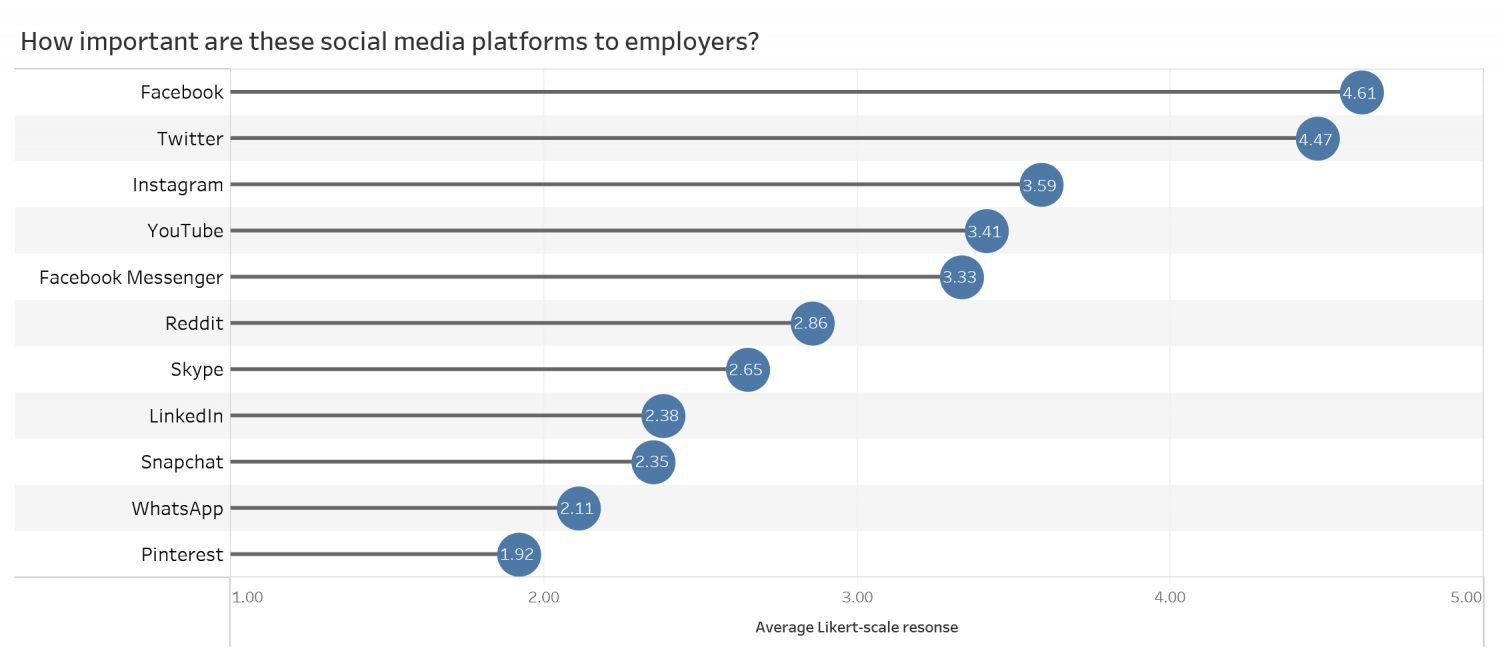

As for the preferred platforms, respondents from Canada’s newsrooms indicated that Facebook and Twitter were by far the most important. As illustrated in the following graphic, when asked which platforms they felt were most important, Facebook had the highest overall average score on the Likert scale (where 1 was “unimportant” and 5 was “extremely important”), followed by Twitter, Instagram and YouTube.

The focus on social media is understandable. According to the 2017 Canadian Digital News Report from the Reuters Institute, 48 per cent of Canadians cited social media as a source for news, compared with 70 per cent for TV, 33 per cent for print and 28 per cent for radio. (Online was cited by 76 per cent, though this included social media.) In other words, news organizations have made it a priority to engage with their audience on social media platforms, and evidently expect young journalists to play a role in this.

This data was collected just before the reporting on Cambridge Analytica became widespread in mid-March 2018. The rest of that year saw many revelations about bots, foreign actors and misuse of private data. It was, as Vox put it, Facebook’s “very bad year.”

It’s too early to tell what impact the revelations of the past year will have on the attitudes towards Facebook and other social media platforms in Canada’s newsrooms. But for the time being, it would appear that most young, aspiring journalists will need to be adept at navigating this complicated and fraught space.