I hadn’t been this excited about a stamp since I collected them back in Grade 6.

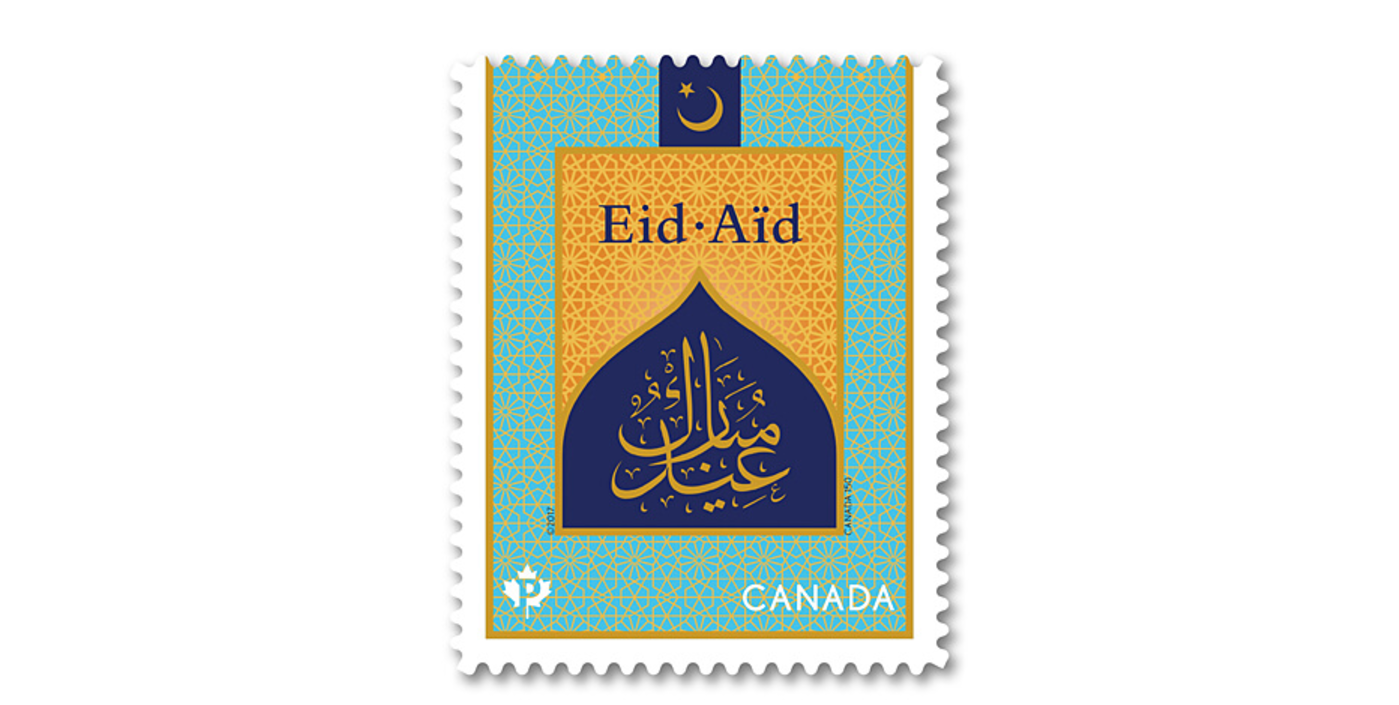

Canada’s first commemorative Eid stamp was unveiled just days before the holy month of Ramadan was set to start this May. I caught one of two launch events in Montreal. I expected to see Quebec’s mainstream media outlets well represented. But there was not a single journalist, beyond ethnic media, in attendance.

It reminded me of last summer, when the organization I work for, the National Council of Canadian Muslims (NCCM), along with community representatives, was holding six simultaneous press conferences across the country to launch the Charter for Inclusive Communities, a document that reaffirms Canadians’ commitments to inclusion and to express opposition to all forms of hate and discrimination. The launch was covered extensively in all but one province: Quebec.

Quebec media, it seemed, was only interested in Muslim stories when there was a bad-news angle.

At a 2016 NCCM youth workshop in Montreal exploring Islamophobia in the media, 94 percent of participants said they felt media portrayals of Muslims in Quebec were negative. This was the highest of Ontario, Alberta, and Manitoba, where we held similar workshops. “The media either intentionally or indirectly portray Muslims as outsiders [or] a threat,” noted one Montreal participant. “They still don’t have the literacy and awareness.”

This reality came into sharp focus following the tragic terrorist attack on a Quebec City mosque on January 29. Politicians, media, and community members alike immediately pointed to the province’s media landscape as a key driver of anti-Muslim attitudes. It was clear that the media landscape—specifically the French-language media—had been too often scapegoating, fear mongering, and promoting stereotypes about Muslims.

Universite Laval’s Colette Brin says the province’s shock-jock radio hosts frequently target minority groups, especially Muslims. “There’s this strong discourse [against] people who they see as wanting to change society, who are asking for special rights,” Brin told The Canadian Press following the massacre. “There’s the fear of Islamic terrorism and the generalization that the Muslims’ Islamic faith in general is the problem.”

This has human rights implications. Galvanized by a far-right anti-Muslim group with a strong presence on Facebook, less than a handful of residents in Saint-Apollinaire voted this past July to reject the establishment of a Muslim cemetery. That was enough to scuttle the proposal.

Part of the problem is a lack of media representation. “[The media] don’t have information about real Muslims. They don’t ask Muslims about the real Islam,” a regular congregant at the Quebec City Islamic Cultural Centre, the site of the attack, told journalists. One host working for radio poubelle (literally “trash talk radio”) admitted that in all the years he’d been talking about Muslims, he’d never even invited a single community member on his program. That admission spurred at least one community activist to reach out and urge radio stations to invite Muslims onto their airwaves. There was only nominal interest, which quickly fizzled out.

Nevertheless, community members do acknowledge a change. “It made us all stop, breathe and do some deep thinking,” writes Montreal activist and interpreter Nermine Barbouch in an email. “Many haters, racists, and Islamophobes have even changed their minds and views. Regardless of their opinion on their fellow Canadian citizens of Muslim faith, they… did not want to be part of this crime and they did not want their words and [Facebook posts] to inspire other haters to insanity.”

Haroun Bouazzi, president of Association des Musulmans et des Arabes pour la Laïcité au Québec, agrees. “There is more sensitivity,” he says.

Individuals with anti-Muslim biases also seem to be getting less air time, says Shaheen Junaid, a Montreal board member with the Canadian Council of Muslim women. “The deaths of our six brothers was not in vain,” she says, seeming hopeful.

Public perceptions seem to be changing, too. Polling by Angus Reid show an upswing in positive attitudes toward Muslims in Quebec; doubling between 2009 and 2017, with the most positive level recorded shortly after the attack.

This doesn’t surprise Sameer Zuberi, a long-time Montreal resident who also works to promote greater understanding among diverse communities. “We were in the papers for a full week, being humanized on every page of the paper,” he says. “The average person who doesn’t have any deep-seated prejudices had their eyes open and it counter balanced to some extent the years of negative media on Quebec Muslims.”

Still, Zuberi says, Canadian media needs to recruit more Muslim journalists—and not just those writing about their own faith. At the Montreal Gazette, for instance, popular blogger Fariha Naqvi-Mohamed began writing a monthly column following the attack in Quebec City. Her most recent columns include reflections on the community spirit that emerged during the devastating floods that swept through parts of Quebec, as well as a profile of Big Brothers, Big Sisters of the West Island.

But it shouldn’t take a tragedy to convince media outlets that more positive coverage is necessary to help foster cohesive communities. Given mainstream media’s struggle to make a profit, reflecting diverse audiences—and therefore attracting more revenue—would be an obvious priority.

As for me, I’ll be out buying my commemorative stamp that too few Quebecers will likely know about or appreciate—unless our own communities shout the good news from the rafters.

This story was originally published by THIS magazine, and is republished with the author’s permission.

Amira Elghawaby is an award-winning journalist and human rights advocate. Along with frequent appearances on Canadian and international news networks, Amira has written and produced stories and commentary for CBC Radio, the Ottawa Citizen, the Toronto Star, the Literary Review of Canada, and the Globe and Mail. Amira spent five years promoting the civil liberties of Canadian Muslims as human rights officer and later, as director of communications, at the National Council of Canadian Muslims (NCCM) between 2012 to the fall of 2017. Amira obtained an honours degree in Journalism and Law from Carleton University in 2001.