Abdullah Shihipar is the first-ever J-Source/CWA Canada Reporting Fellow. Shihipar has written about the media and social issues for numerous publications, including the Globe and Mail, Quartz, VICE, CANADALAND, Torontoist and NOW Magazine.

In late 2016, Oliver Stone’s film Snowden was released in theatres. The movie told the story of the whistleblower, Edward Snowden and his leak of classified documents from the NSA. The movie documents how exactly the journalists behind the story came together from different outlets and backgrounds to get the biggest leak in recent history out to the public.

This type of collaboration may seem like the stuff of movies, but in reality journalists often work together on stories. But in today’s competitive atmosphere, how exactly does collaboration occur? What does that process look like?

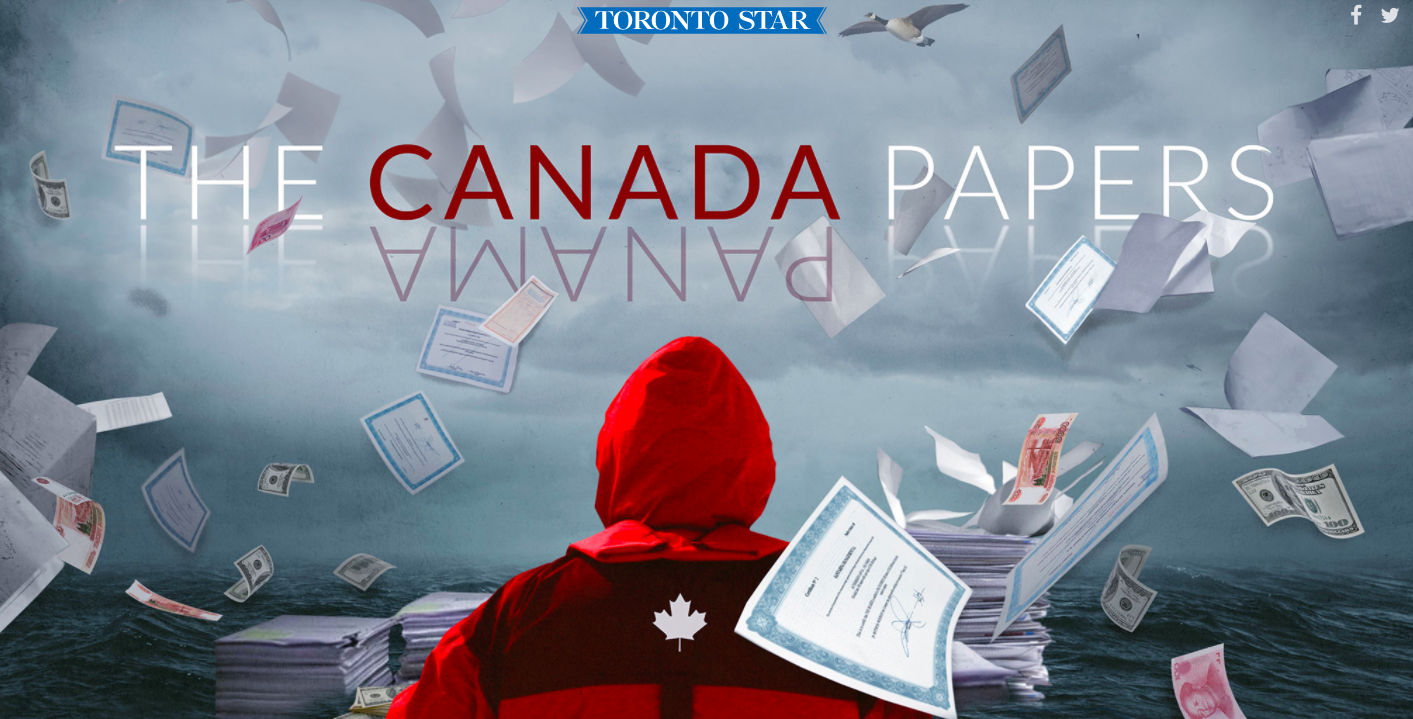

In January of this year, the CBC and the Toronto Star published a three-part investigative report entitled “The Canada Papers,” which showed that tax advisers around the world were helping clients cheat their way out of taxes by using shell companies in Canada. This report came out of the Panama Papers leak of 2016, which was handled by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, of which the CBC and Toronto Star are members. This meant reporters from the Star and the CBC were working together from the start.

Dave Seglins, a reporter for the CBC who worked on the story, told J-Source being in the ICIJ demands collaboration. “The leaks are so huge — it demands many, many journalists to pour through all of the information,” he said. “By enlisting partners in countries around the world to do the research the ICIJ is able to outsource the digging for gold with local journalists who can bring their own sources, smarts and knowledge to bear on massive amounts of data.”

Seglins noted that this specific partnership occurred long after the initial Panama Papers stories were published through the ICIJ.

“It was a smaller collaboration between Canadian media partners. We worked together to comb through materials, to determine which stories we’d tell, and set a publication date together reaching consensus depending on organization’s needs and hopes,” he said.

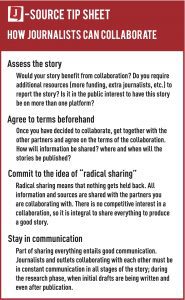

For any collaboration to work, Seglins said there needs to be an agreement on ‘radical sharing’; the idea that all information is shared and nothing is held back. His counterpart at the Toronto Star, investigative reporter Robert Cribb, agrees.

“Generally speaking, the terms and conditions are laid out well in advance. We agree on publication dates, how to approach subjects, distribution of work, how to handle interviews requiring television and print,” said Cribb.

They key rule, according to Cribb, is to share everything. “We typically work in shared drives that allow us to put everything we get in one place for review by all. Video, images, graphics — everything is shared. Each organization is responsible for its own stories. But we share final versions to ensure the key information does not conflict and that we have each drawn from the same facts and figures.”

According to Seglins, the process of collaboration usually ends up with journalists coming to similar conclusions about angles and focus, but this isn’t always the case. Sometimes outlets may choose to report findings differently, and while this may cause some contention, it does not signal the end of collaborative efforts. If different outlets choose to report on the same story with the same focus, this poses no problem said Seglins.

“In fact, it only strengthens the impact of the final publication,” he said.

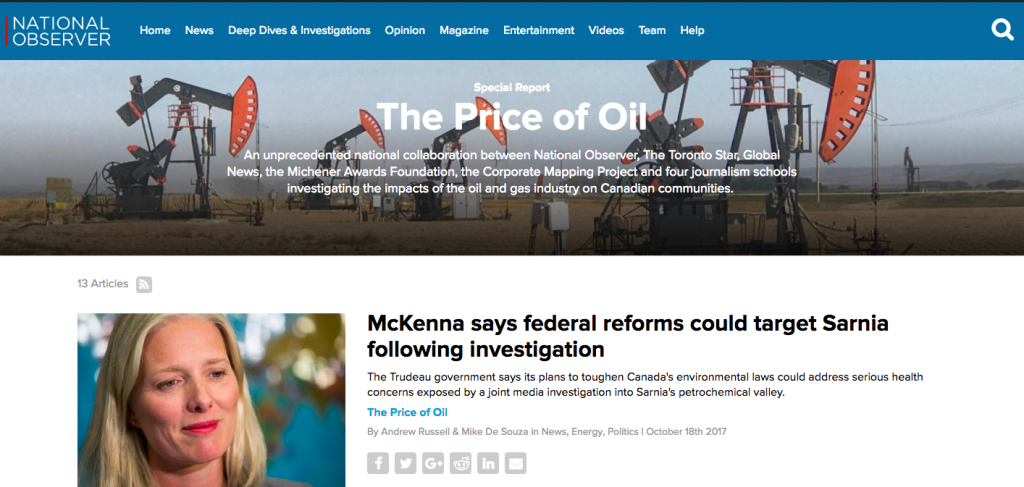

This year, four Canadian universities — UBC, Concordia University, Ryerson University and the University of Regina — came together with the Toronto Star, the National Observer, Global News, the Corporate Mapping Project and the Michener Awards Foundation to investigate how the oil and gas industry is affecting Canadian communities.

The joint investigation, titled “The Price of Oil,” started publishing on various platforms in October. The first two stories revealed how the government in Saskatchewan failed to protect and inform the public about the threat of hydrogen sulfide gas. Another story raised questions about the Ontario government’s oversight of industry in the Sarnia region, where industrial pollutants are suspected to have adversely impacted the health of the communities in the region.

The series was years in the making. Both Patti Sonntag, a Michener fellow and managing editor in the New York Times News Services division and Cribb had been separately working to convince Canadian journalism schools to form a collaborative student network, with a view toward establishing a National Student Investigative Reporting Network. When Sonntag was granted funding from the Michener Awards foundation to investigate the oil industry with the Corporate Mapping Project, she and Cribb joined forces. Things started to fall in place in August and September of last year, when the media companies and universities signed on to the project.

This collaboration was unique because it involved student journalists, which brought with it certain challenges, according to Trevor Grant, a lecturer at the University of Regina.

“Over and above the challenge for the university instructors in managing this complex project there was the reality that the students would be going into the field to film and conduct interviews,” said Grant. “A primary challenge was to ensure our students were prepared, editorially and emotionally, to conduct face-to-face interviews with people who had suffered emotional devastation and also to conduct accountability interviews. There was concern about this step, but the accountability interviews were often insightful, informative and engaging.”

Michael Wrobel, a graduate student and journalist based at Concordia University, says the experience was beneficial for all involved;. The newsrooms had student journalists to help out with the extra material, while students were given the opportunity to try their hands at investigative journalism and were able to work with veteran journalists; learning important skills in the process.

“We learned how to scrape and analyze data, file freedom requests, develop sources, and co-create knowledge about a complex and technical subject as part of a team,” he said.

With a story involving a number of different partners, what does the process of publication look like? Elizabeth McSheffrey, a reporter with the National Observer, explained that the publication process is both “wonderful and tricky all at once” and requires constant communication.

“Everyone hits the ‘publish’ button at the agreed upon time, then a social media frenzy ensues. We stay in communication to share feedback we’ve received on the work, craft followup pieces collaboratively and move on to the next chapter,” McSheffrey explains.

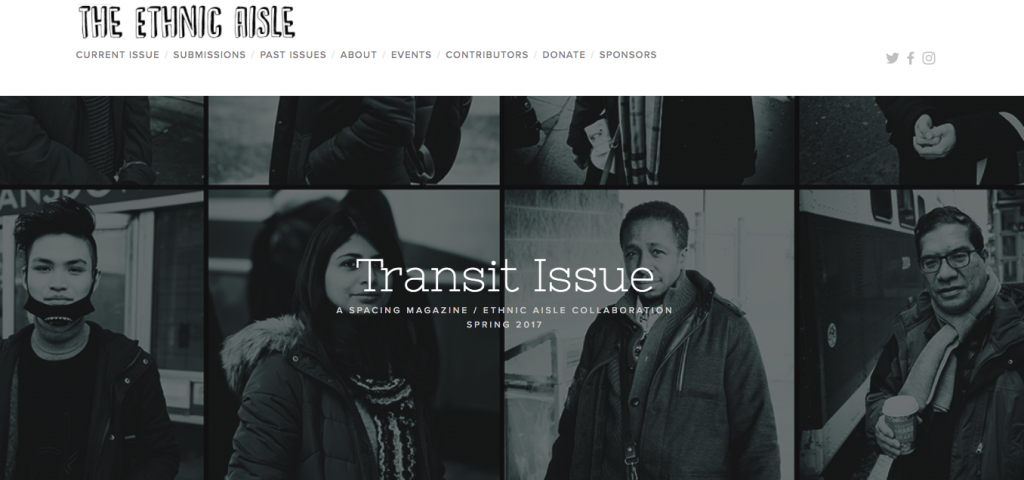

Collaborations don’t always have to be undertaken strictly for the purposes of investigative journalism however. Journalists can come together under a different set of circumstances, like the production of a joint issue between two magazines. This is what the teams at Spacing and The Ethnic Aisle aimed to do when they produced a joint issue on race and transportation in Toronto’s suburbs. The issue was released this past March, online on the Ethnic Aisle’s website and in print issues of Spacing.

Perry King, the managing editor for the issue, said that communication and planning were crucial to the process, especially when the two outlets involved differ in scope and tone.

“Plenty of hurdles exist, but most of them is a matter of communication and planning; keeping on top of writers and creatives, seeking a balance between their creativity and Spacing’s wants as a journalistic organization,” said King. “I had to make clear boundaries on deadlines and have a clear creative conversation, appealing to tenets of the project’s purpose and scope but not taking away from the spirit of the writing itself.”

King cites collaborative work as being crucial to journalism as more freelancers enter the industry.

“Freelancers have relationships with unique stories and beats and newspapers and other traditional mediums have resources — but they don’t often have the means and the platform to bring the most unique stories to the public. That relationship needs to continue to be fostered going forward,” said King.

Collaborations between journalists may prove to be more of a crucial public service.

“If you go into a collaboration, it can’t be for your own glory or that of your news organization: Bylines and credits are shared. This work — the community service — is more important than individual credits and pays off more richly for your organization in the long term,” said Carolyn Jarvis, an investigative reporter with Global News who worked on the Price of Oil series.

Seglins agrees. “I think the public is the winner. And the journalism winds up being much better.”